"Bah! Humbug!" is, perhaps, one of the most famous utterances to issue forth from the mouth of Charles Dickens's exquisite creation, Ebenezer Scrooge.

It first appears in the novella when Scrooge's nephew, Fred, bursts into the counting house and cries, in a cheerful voice, "A merry Christmas uncle! God save you!"

Scrooge, who we have just learnt at length, is a man who does not have an ounce of the spirit of the festive season in him, replies - "Bah! Humbug!"

"Christmas a humbug, uncle!", replies Fred, "You don't mean that, I am sure?"

This causes Scrooge to launch into his tirade about why Christmas is a season to be despised rather than to be embraced and celebrated.

But, what does "Bah! Humbug!" actually mean?

Well to begin with, "Bah!" is simply a demonstration of contempt, and in this context Dickens uses it to show Scrooge's irascibility with his nephew's cheerfulness.

Scrooge would have almost spat the word at his nephew, in order to show his utter disdain for Fred's excitement over its being Christmas

"Humbug", on the other hand, could be used in several contexts at the time.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "humbug", is "deceptive or false talk or behaviour" - as in, "What you just said was humbug."

It could also be used to refer to an act that is intended to deceive and mislead; or as a description of someone who is being willfully false, deceptive or insincere.

In A Christmas Carol, Dickens uses it to suggest fraud, since Scrooge, old curmudgeon that he is, considers the celebration of Christmas, and all the festivities associated with it, to be a total sham.

Over time, however, the word has largely disappeared from the common lexicon, and it is safe to say that if anyone today uses the word "humbug" they will, most probably, have in mind Scrooge's use of it in A Christmas Carol.

Admittedly, it does turn up from time to time in the public arena, perhaps most infamously when Boris Johnson used it in a suitably bad-tempered Parliamentary exchange during a Brexit debate in September 2019.

But, on the whole, if anyone uses it today they will be making some sort of reference to Dickens famous old skinflint's use of it, at a time when people had long been used to seeing it in their newspapers, and hearing it used in everyday conversation.

But, where did it come from?

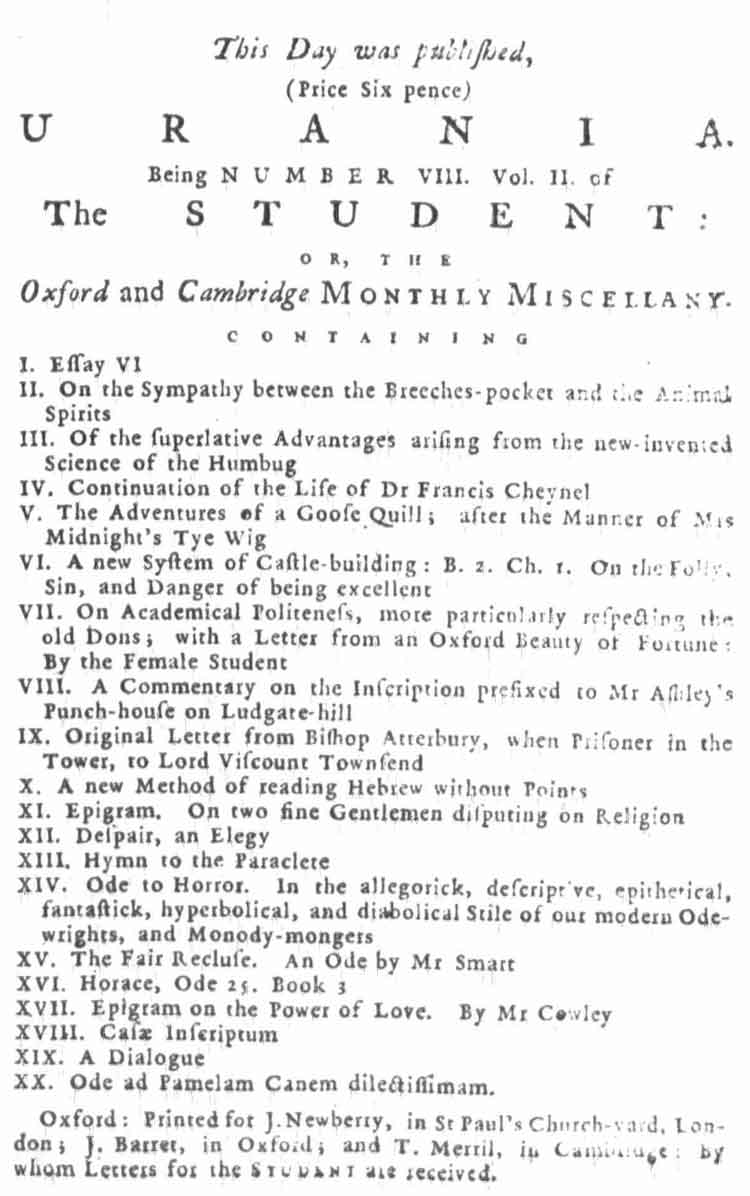

Humbug came into prominence in the mid 1700s, and one of the earliest mentions of it was in The Student, or The Oxford and Cambridge Monthly Miscellany, published in 1751.

The Newcastle Courant carried an advert for the publication in its edition of Saturday, 18th May, 1751, in which one of the articles mentioned was:-

"Of the Superlative Advantages arising from the new-invented Science of the Humbug..."

The Advert From The Newcastle Courant

Copyright, The British Library Board.

The Caledonian Mercury, on Thursday, 8th February 1753, published a story which showed how the "common practice of humbugging" could have tragic consequences:-

"Tuesday last Capt. D--- and Capt. B --- , of the Foot-Guards, fought a Duel behind Montague-Houses, in which the former was mortally wounded.

This unhappy Quarrel was occasioned by the favourite Maxim of Humbugging, which is become too common, even among People of Quality."

The Scots Magazine, on Monday, 1st October, 1753, published the following article in which humbug was used in the context of a fraudulent or misleading act:-

"I was animated to attempt yet greater excellence. I learned several feats of mimicry of the under-players, could take off known characters, and humbug with so much skill as sometimes to take in a knowing one."

By 1754, the word was in common usage to describe misleading entertainments and the publicity used to promote them, as is evident in the following story which appeared in The Oxford Journal Saturday, 7th September, 1754:-

"As an instance of the present Depravity of some of the lower sort of People, even in their Entertainments, we find, in one of the daily Papers, an Invitation to those who can delight themselves with the beastly Spectacle, to attend a Fellow that is to divert them, by devouring, in one Hour, fourteen Pounds of Bacon, two Quarts of Beans, a large Cabbage, a Quartern Loaf, some Apple Pye, and a Gallon of Strong Beer, for a Wager.

And Yesterday a great Number of People assembled together at Dalston, to see the famous Performance at the Sign of the Red Cow, near Hackney, but it appearing to be a Humbug, the Populace were so incensed, that they took him to the Brook and severely ducked him."

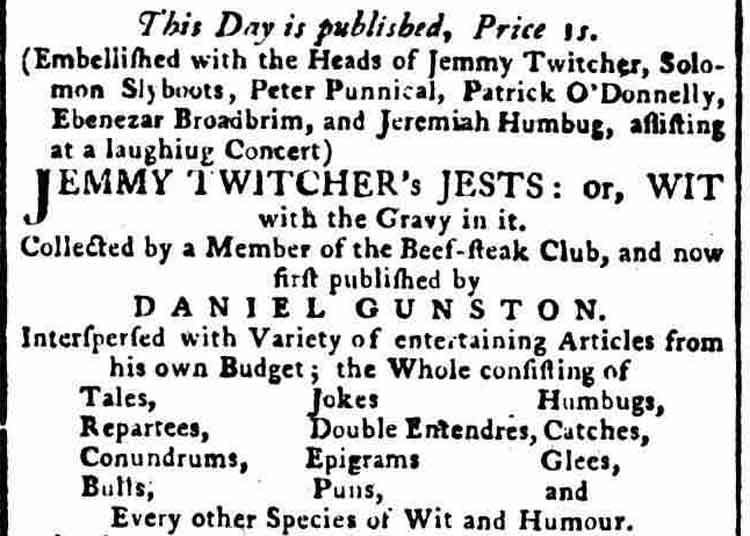

By the 1770s, humbug had become immensely popular as a word, so much so that many joke books advertised that they would be featuring "humbugs" as well as their usual offerings.

One such joke book, which was advertised in the Reading Mercury was Jemmy Twitcher's Jests, which advertised that its contents consisted of, among other things, "Tales, Jokes and Humbugs."

In addition, plays were often accompanied by farces with titles such as The Intriguing Footman, Or The Humours Of Humbug, which featured characters with names like "Harry Humbug."

The Advert For Jemmy Twitcher's Jests From The Reading Mercury Monday, 16th April, 1770.

Copyright, The British Library Board.

By the 1780's the word was frequently used to describe anything that was considered to be a fraud on the public, in which context it was used in the following article, which appeared in The Derby Mercury on Thursday, 15th July, 1785:-

"The People of this Country have been so often humbugged, that it was not to be wondered at that not more than 150 Persons were found foolish enough, Yesterday, to part with their half Crowns, to see what was so pompously announced in all the Papers, viz. That between two and three o'clock, at Blanchard's Aerostatic Academy an Italian Gentleman would descend from a prodigious Altitude, by Means of a Parachute, and was so perfectly sure of his Safety as to play a favourite Tune on the Violin during his Descent."

On Saturday, 11th October, 1788, The Northampton Mercury, published a story concerning losses made by Lord Drogheda at the card tables of the spa town of Buxton:-

"Lord Drogheda, on his late Visit to Buxton, introduced a new Game called Humbug - a Kind of two-handed Whist.

His Lordship took some Pains in teaching it to an elderly Lady of Quality, who, in the Course of a Week, grew so perfect an Adept, as to humbug the noble Lord out of no less Sum than 1400 Guineas at his own Table."

On Friday, 1st February, 1793, The Stamford Mercury published the following article aimed at explaining how universal the use of the word "humbug" had become, and providing its readers with some instances in which it could be used:-

"The most comprehensive word in the English language (though the most trivial in sound) is that of humbug. It is of so copious a nature, as to comprehend in itself almost every science, but particularly law and physic. Every day's practice gives instances of its analogy to both.

The law may be called humbug, because it eases the rich man of his wealth - the poor man of his Liberty.

Large sums have been spent to find out its meaning, but there is none so explanatory as that of humbug.

Physic is a humbug because the practice more often kills than cures, and art is supplied for Dame Nature, till the expiring fee ends with the expiring patient.

It is true the lawyer humbugs you out your property, but the physician does more, as he humbugs you out of your life.

The Parliament-house is a humbug, because it taxes the constituent, and enables the representative, with privilege of law, to run into debt, but makes no laws to pay, therefore the constituent is humbugged out of his vote, and in return, with a taxation of seven years session; and the comfortable reflection left is, that if he has any demands for the expense of choosing him, and not take the privilege of it.

The Admiralty may be called humbug, as it fits out fleets for sea, you may always see in sight, yet makes John Bull pay for battles that are never fought.

The theatre is humbug, because it not only makes you pay for every species of fiction, but robs you of your understanding, imposing the works of children on men.

The whole theatre of the world may be called humbug, and he or she that can contrive to get through life without being humbugged, may be justly called "Rara Avis", and such an one ought to have a monument in Westminster Abbey erected to his memory, as an example to posterity, that he lived and died in this enlightened age without being humbugged."

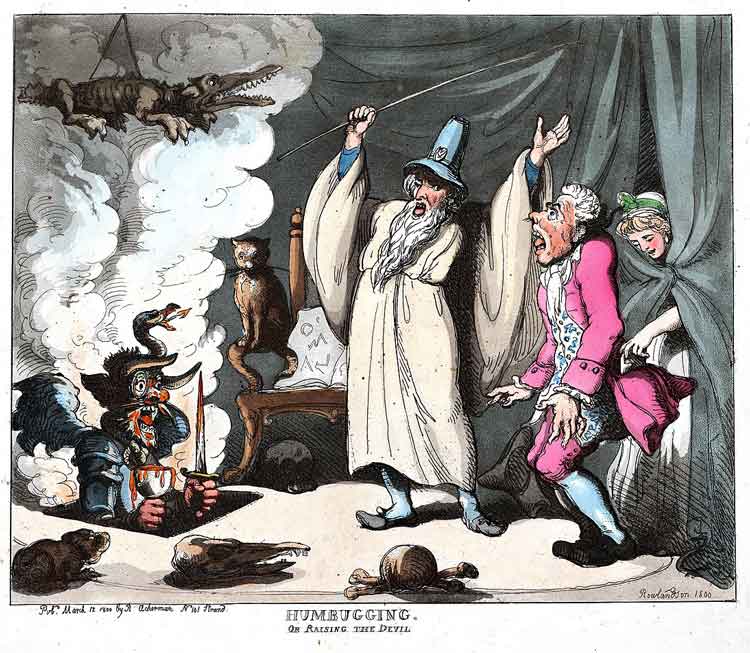

Humbugging, in the context as an act intended to both deceive and distract, was the subject of Thomas Rowlandson's satirical cartoon of 1800, which was titled Humbugging Or Raising The Devil.

The cartoon depicts a bogus wizard who is raising his wand to conjure up a hideous-looking figure that rises from a trap door in the floor amidst a swirling cloud of smoke.

The grotesque spectacle is being watched by a terror-stricken man whose distracted state is being exploited by a woman who is picking his pocket from behind the curtain.

By the early 19th century, "humbug" was being used increasingly in a political context; and, with the Napoleonic wars raging, it was even used to describe the actions of the man who was destined to become a national hero - Lord Nelson, as is demonstrated by the following article, which appeared in The Morning Post on Saturday, 15th August, 1801:-

"The bustle in the ports of Holland continues; and a letter from Brussels represents the preparations against this country as formidable. But this is no doubt "a humbug of the English Minister's."

Lord Nelson is also "humbugging."

Our Deal letter of Thursday says:- Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson, in His Majesty's ship Medusa, with the Galgo sloop of war, Explosion bomb, and Express advice-boat, arrived last night, and remain.

A great many flat-bottomed boats have been taken off from His Majesty's naval store-yard here, this morning, to the armed ships Lord Nelson's command, and his Lordship has several alongside of his own frigate."

This, according to one of the Journals, is all "Ministerial Humbug."

By the 1830s, the word "humbug" was frequently being used to describe fraudulent acts perpetrated on members of the public by what we today might refer to as grifters. An example of this use of the word appeared in the following article concerning a case that had been heard at the Mansion House Police Court, and which was reported in The Globe, on Wednesday, 11th June, 1834:-

"The Lord Mayor stated that Mr. Ady, the person who has so long been in the habit of writing letters to the namesakes, in all quarters of the globe, of parties mentioned in the unclaimed dividend book in the Bank, informing them that he will communicate something to their advantage upon being paid twenty shillings, still persevered in his endeavour to humbug people. ...The Lord Mayor stated that he had received a great number of letters relative to Ady, some of which called upon his lordship, in the most peremptory and indignant manner, to put a stop to humbug of so disagreeable a kind...."

Humbug was also being used a lot in the newspapers during the 1830s and 1840s to describe the deceitful statements and/or intentions of politicians; and, since Dickens had begun his career as a parliamentary reporter in the 1830s, he most certainly would have been aware of its political connotations and of its usage by Members of Parliament to describe statements that they felt were blatantly false or misleading.

The Leicester Chronicle reporting on a debate in the House of Lords, used the word in just such a political context:-

"Mr. Kearsley rose, and directly he did so there was great laughter and cries of Hear. He said, I have often considered the hon. member for Middlesex a useful check to the extravagance that would otherwise be indulged in (a laugh); but after what I witnessed five minutes ago, I must put down his conduct as perfect humbug..."

The Bristol Mirror on Saturday, 26th November, 1842, provided its readers with a possible origin of the word:-

"Everybody, perhaps, is not acquainted with the etymology of the word Humbug. It is a corruption of Hamburgh and originated in the following manner:- During a period when war prevailed on the Continent, so many false reports and lying bulletins were fabricated at Hamburgh, that at length, when any one would signify his disbelief of a statement, he would say, "you had that from Hamburgh;" and thus, "that is Hamburgh," or "Humbug," became a common expression of incredulity."

The Coventry Herald on Friday, 22nd July, 1842, managed to pre-empt Scrooge's combining of Bah and Humbug by eighteen months, when it used the phrase "bah, humbug" to dismiss a political rally:-

"Friends and Fellow Townsmen. A large placard made its appearance on Saturday, headed "Starvation!" in large type, calling upon the people of Coventry to meet in their assembled thousands, in the County Hall at twelve o'clock, Tuesday, the 19th day of July, 'to take into their most serious consideration the present alarming state of the Country, and to adopt the only remaining remedy left, Complete Suffrage.' (Bah! complete humbug!)"

Thus, when Dickens came to write A Christmas Carol, in October, 1843, the word humbug was in common usage and his readership would have immediately grasped the fact that Dickens's use of it was just another demonstration of Scrooge's utter contempt for Christmas and all its frivolities.

The Fife Herald, on Thursday, 22nd May, 1845, explained the circumstances under which an untruth could be classed a humbug:-

"We must define humbug. It is not naked untruth.

A draper's assistant, who tells a lady that a dress will wash when it will not, does not humbug - he merely cheats her.

But if he persuades her to buy a good-for-nothing muslin, by telling her that he has sold such another to a Duchess, he humbugs her, whether he speaks truly or not. He imposes an inference in favour of his commodity, through her large vanity, upon her small mind.

Humbug thus consists in making people deceive themselves by supplying them with premises, true or false, from which, by reason of their ignorance, weakness, or prejudices, they draw wrong conclusions."

And so, as you can see, humbug was a commonly used by the time that Dickens wrote his festive masterpiece, and his readers would have understood the context of his usage of it far more readily than we do today.

Scrooge uses it several times in his angry exchanges with his nephew, Fred, as they debate the benefits of Christmas:-

"A merry Christmas, uncle! God save you!" cried a cheerful voice.

It was the voice of Scrooge's nephew, who came upon him so quickly that this was the first intimation he had of his approach.

"Bah!" said Scrooge, "Humbug!"

He had so heated himself with rapid walking in the fog and frost, this nephew of Scrooge's, that he was all in a glow; his face was ruddy and handsome; his eyes sparkled, and his breath smoked again.

"Christmas a humbug, uncle!" said Scrooge's nephew. "You don't mean that, I am sure?"

"I do," said Scrooge. "Merry Christmas! What right have you to be merry? What reason have you to be merry? You're poor enough."

"Come, then," returned the nephew gaily. "What right have you to be dismal? What reason have you to be morose? You're rich enough."

Scrooge having no better answer ready on the spur of the moment, said "Bah!" again; and followed it up with "Humbug.""

Humbug turns up again at the point where Marley's ghost ushers in the beginning of Scrooge's supernatural encounters.

Having arrived home, Scrooge sits close to his "low" fire, the fireplace around which is "paved with quaint Dutch tiles, designed to illustrate the scriptures...If each smooth tile had been a blank at first, with power to shape some picture on its surface from the disjointed fragments of his thoughts, there would have been a copy of old Marley's head on every one."

Scrooge's response to this is, "Humbug!" In other words, Scrooge just doesn't believe what he is seeing.

There then follows the scene where the disused bell begins to ring, followed by every other bell in the house also ringing.

It is then that he hears a clanking noise, deep down below; "as if some person were dragging a heavy chain...Scrooge then remembered to have heard that ghosts in haunted houses were described as dragging chains."

The clanking noise then comes up the stairs and heads straight for Scrooge's room, whereupon Scrooge dismisses it contemptuously. "It's humbug still! I won't believe it."

At this point Marley enters through the closed door, and we are treated to the scene where Scrooge tells him why he doesn't believe in him, ending his explanation with, "Humbug, I tell you! Humbug!"

Dickens uses humbug in this scene to stress that Scrooge doesn't believe in ghosts, and thinks that Marley's appearance is simply his senses misleading or playing tricks on him.

Of course, nowadays, the word humbug is, more or less, associated exclusively with Dickens's curmudgeonly old miser; and, with the exception of Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson, few people use it in any other context than to remember Scrooge's irascible outbursts in A Christmas Carol.

But now, whenever you hear it being used, you wil be able to assume a countenance of superiority and, with a knowing nod, tell the person who has used it of its true meaning and origins.

So, one last time and all together now .... Bah! Humbug!